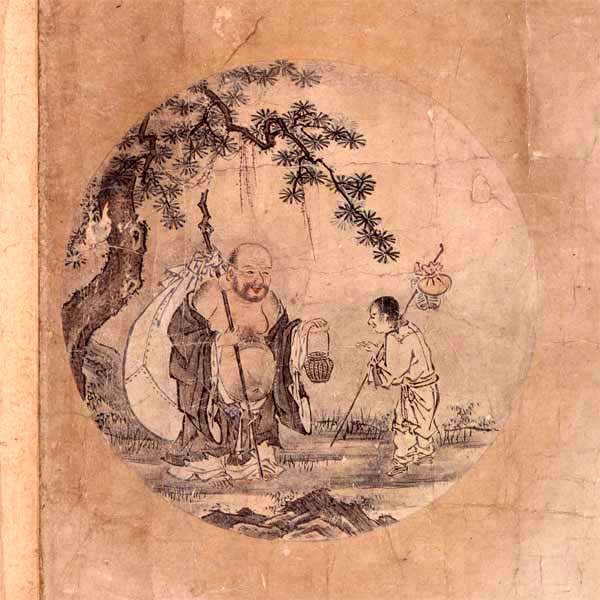

Step Eight – Both Self and Ox Forgotten

The Third Dharma Realm

Whip, rope, person, and bull — all merge in No-Thing. This heaven is so vast no message can stain it. How may a snowflake exist in a raging fire? Here are the footprints of the patriarchs.

[su_spacer size=”30″]

The third dharma realm is the dharma realm of the Pratyeka Buddhas.

The central practice is to apply the super power mindfulness developed by the above steps to the Doctrine of Dependent Arising.

The Pratyeka Buddha is defined as a being who attains Buddhahood even when there is no Buddha in the world. In other words, a Pratyeka Buddha is a self-taught Buddha.

However, Pratyeka Buddhas can also arise when there is a Buddha in the world. They are then considered to be beings enlightened by conditions.

Just as the realm of the hungry ghost is perhaps best understood as being a transitional realm between the hell realm and the animal realm, we can also think of the Pratyekabuddhas as occupying a realm above that of the Arhats but below that of the Bodhisattvas.

Master Yasutani says: At the eighth stage, we come to realize the fact that this “I” (self), which has been seeking, and the essential self (ox), which has been the object of our search, did not exist at all. Thus, both self and ox are forgotten.

[su_spacer size=”30″]

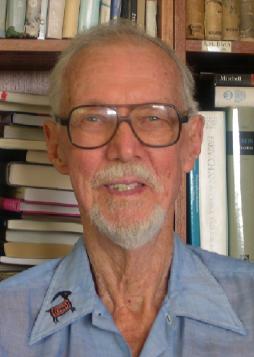

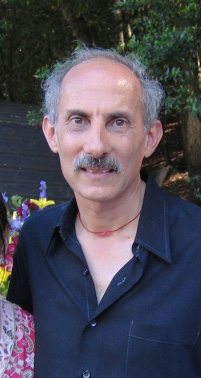

Harada Roshi, teacher of Yasutani Roshi

(1871-1961)

This isn’t the kind of statement we can understand with the critical thinking mind. For us to say that neither we nor our minds exist is nonsense to our rational, thinking mind.

The original set of the Ox-Herding Pictures ended with the eighth “drawing.” It was a blank space, indicating that anything that was depicted about the eighth and final stage would be misleading.

“This heaven is so vast, no message can stain it” means that any words or drawings about the eighth and final stage were meaningless. Words and drawings are mere snowflakes that can’t exist in a raging fire.

The circle (enso) indicating no beginning of practice and no ending to enlightenment was added as the eighth drawing when the eight Ox-Herding Pictures were augmented to include the ninth and tenth drawings.

Apparently, the augmentation took place when someone decided that forgetting the self and the ox, i.e., eliminating the duality between self and goal, placed the practitioner not in nirvana but in the neighborhood of nirvana.

The ninth step of reaching or returning to the source was added as was the tenth step of returning to the marketplace to indicate that the ideal of the Bodhisattva – teaching and helping others while refraining from entering into Nirvana until all others have done so as a result of such teaching – was the true final step, not Buddahood.

However, we rank the first dharma realm of the Buddhas above the second dharma realm of the Bodhisattvas. Ranking a Bodhisattva above a Buddha seems to be part of the Mahayana’s attempts to “trump” the “Hinayana” or “lesser vehicle” (Theravada) by announcing that one who returns to teach is above a Buddha who simply disappears into Nirvana.

A Bodhisattava, however, is a Buddha-to-be, so it is hard to see how a future Buddha is to be more revered than an actual Buddha. And the Mahayana assertion that a Theravada Buddha vanishes and becomes meaningless but that a Mahayana Buddha returns to teach and to rescue beings from the hell realms – which a Theravada Buddha supposedly doesn’t do – seems to emanate from an ill will toward the “Hinayana.”

I have attended so-called Buddhist events at Thai (Theravada) temples where the slaughtered bodies of animals are served up in copious quantities, and I certainly understand the origins of the Mahayana disdain for the Theravadans.

If the Theravadans would start following the precept against killing, the two major schools of Buddhism could re-unite. Both schools could then practice Theravada tranquil wisdom meditation to develop the super power mindfulness needed to see the doctrine of dependent arising, both forward and backward, and to solve Mahayana/Zen koans.

Just as the Christians have limited “Thou Shalt Not Kill” by interpreting that commandment to mean “Thou Shalt Not Kill Human Beings And Even That Is OK When The Government Wants A War And Thou Shalt Kill All Animals That Thou Thinketh To Be Tasty When Cooked,” (real carnivores eat meat raw) so have the Theravadans limited the first precept to non-killing of human beings.

The Buddha, who used the strongest terms when condemning the wanton slaughter of animals, mentions multiple times in the Pali Canon that an enlightened being sees dependent arising, both forward and backward, and that no enlightenment has occurred if the being has not seen dependent arising, both forward and backward.

Intellectually understanding the Doctrine of Dependent Arising/Origination has nothing at all to do with knowledge of the doctrine in the conventional sense. True understanding is non-intellectual and arises from having coursed through the four dhyanas/jhanas and the four immaterial attainments and applying the super power mindfulness so developed to the doctrine in a non-intellectual, non-verbal way.

There are a number of sutras/suttas that mention the Doctrine of Dependent Origination. The Buddha said that to understand the Doctrine of Dependent Origination is to understand the Four Noble Truths.

The hyperlinked article is lengthy but well worthy of our study at the Advanced Zen level. It is also available in book form under the title Dependent Origination: Buddhist Law of Conditionality.

In a verbal way, this is the doctrine in the forward or arising direction:

1-2. From ignorance (avijja) arises volition (sankhara); (avijja paccaya sankhara)

2-3. From volition (sankhara) arises consciousness (vinnana); (sankhara paccaya vinnanam)

3-4. From consciousness (vinnana) arises body and mind (nama-rupa); (vinnana paccaya nama-rupam)

4-5. From body and mind (nama-rupa) arises the six senses (salayatana); (nama-rupa paccaya salayatanam)

5-6. From the six senses (salayatana) arises contact (phassa); (salayatana paccaya phassa)

6-7. From contact (phassa) arises feeling (vedana); (phassa paccaya vedana)

7-8. From feeling (vedana) arises craving (tanha); (vedana paccaya tanha)

8-9. From craving (tanha) arises clinging (upadana); (tanha paccaya upadanam)

9-10. From clinging (upadana) arises becoming (bhava);

(upadana paccaya bhava)

10-11. From becoming (bhava) arises birth (jati); (bhava paccaya jati) and

11-12. From birth (jati) arises old age and death (jaramaranam); (jata paccaya jaramaranam).

From old age and death (jaramaranam) arises sorrow, lamentation, pain, grief and despair (soka-parideva-dukkha-domanassupayasa nirujjhan’ti). (jaramaranam paccaya soka-parideva-dukkha-domanassupayasa nirujjhan’ti)

Here is the doctrine in the ceasing direction:

1-2. When ignorance (avijja) ceases, then volition (sankhara) ceases;

2-3. When volition (sankhara) ceases, then consciousness (vinnana) ceases;

3-4. When consciousness (vinnana) ceases, then mentality-materiality (mind and body) (namarupa) ceases;

4-5. When mentality-materiality (mind and body) (namarupa) ceases, the six sense bases (salayatana) cease;

5-6. When the six sense bases (salayatana) cease, then contact (phassa) ceases;

6-7. When contact (phassa) ceases, then feelings (vedana) cease;

7-8. When feelings (vedana) cease, then cravings (tanha) cease;

8-9. When craving (tanha) ceases, then clinging (upadana) ceases;

9-10. When clinging (upadana) ceases, then becoming (bhava) ceases;

10-11. When becoming (bhava) ceases, then birth (jati) ceases; and

11-12. When birth (jati) ceases, then old age and death (jaramaranam) cease.

When old age and death cease, then sorrow, lamentation, pain, grief and despair (soka-parideva-dukkha-domanassupayasa nirujjhan’ti) cease.

The Buddha defined Nirvana as the highest happiness.

By the way, he never said “old age, sickness and death.” He said “old age and death.”

Sickness is optional.

[su_spacer size=”30″]

Palolo Zen Center, home of the Honolulu Diamond Sangha

Step Nine – Reaching the Source

The Second Dharma Realm

Too many steps have been taken returning to the root and the source. Better to have been blind and deaf from the beginning! Dwelling in one’s true abode, unconcerned within and without – The river flows tranquilly on and the flowers are red.

[su_spacer size=”30″]

The second dharma realm is the dharma realm of the Bodhisattvas, the highest ideal of the Mahayana school.

The central practice is the solving of Zen koans as the antidote to conceit, restlessness, and ignorance (the eighth, ninth, and tenth fetters, respectively).

If we are not familiar with koan practice, we can read Albert Low’s Working with Koans in Zen Buddhism and John Daiso Loori’s Sitting With Koans.

Even though the first dharma realm is the dharma realm of the Buddhas, the Ox-Herding pictures depict the first dharma realm as a Bodhisattva entering the marketplace to teach.

The Theravada ideal of a Buddha who disappears from all dharma realms, never again to be seen or heard from, did not sit well with the Mahayana school. In the Mahayana, the ideal of the Bodhisattva who returns to teach is the highest ideal.

A being of infinite compassion would not disappear, leaving the unenlightened to their sufferings. No compassionate being could enjoy heaven knowing that the hell worlds were occupied.

The Theravada school replies that the Buddha left his teachings behind and thus expressed his infinite compassion.

And that the hell worlds are impermanent and everyone will attain Nirvana someday.

The Zen sect replies that everything is mind alone, i.e., the dharma realms are different levels of awareness. A Buddha can visit the dharma realm of Bodhisattvas.

Reaching or more accurately, returning to the source, occurs when the Zen practitioner is “unconcerned within and without.” According to the commentary that accompanies the ninth picture, all notions of subject and object, self and other, inside and outside, gain and loss, life and death, up and down, beginning and ending, are gone.

Reaching the Source, also known as Breaking Through the Zen Barrier, is the hardest thing an untrained human being can do.

However, we who have honestly followed the first eight steps of this course are no longer untrained.

Jerry Seinfeld tells a story about horses talking to one another after a race. One horse says to another: “After crossing the finish line, I noticed it was the same as the starting line. I could’ve won the race just by staying where I was!”

The traditional commentary on this ninth stage is that when one continues to practice, one breaks through the Zen barrier and realizes that one has returned to the starting line and that one has traveled far just to go nowhere.

It is discouraging at first to learn that when we experience a full-blown, fully matured enlightenment after years of arduous practice, we have merely returned to the starting point. Mountains and rivers are again just mountains and rivers.

[su_spacer size=”30″]

Buddhist temple on the peak of Wolf Hill

Even the verse that accompanies the ninth picture of the ten ox-herding pictures seems to have been written in anger, an emotion that an awakened master would not be expected to exhibit:

Too many steps have been taken returning to the root and the source. Better to have been blind and deaf from the beginning!

But the end of the verse throws more light:

Dwelling in one’s true abode, unconcerned within and without – The river flows tranquilly on and the flowers are red.

(End of verse) This means that the river doesn’t need us to perceive it nor do the flowers. There is no self within to observe the river and the flowers, and no river and flowers without. We have here an affirmation that the dichotomy of subjective/objective doesn’t exist. To see this, we need to return to the source.

No Bodhisattva who is a real Bodhisattva cherishes the idea of an ego-entity, a personality, a being, or a separated individual.

When we have followed the preliminary steps of Beginning Zen and all sixteen steps of tranquil wisdom meditation every day until the practice has become second nature, we have climbed the One Hundred Foot Pole and are ready to leap. Our practice has created the conditions that allow us to break through the barrier, reaching the source.

Too many steps have been taken; that means we have been thinking too much.

The Buddha conveyed in words the sixteen steps that he experienced after first placing mindfulness up front. Obviously, he did not undergo those sixteen steps the way we do – thinking about them, rather than trusting them to flow naturally.

There are no “steps” if we get ourselves out of the way and let the meditation deepen all by itself. The Buddha’s meditation was an analog process but when it is described in words it becomes a digital, step-by-step process.

We work hard to master the sixteen steps and sometimes we do feel that too many steps have been taken. However, we have to practice until we stop thinking about the steps, letting them flow naturally, one after the other without our mental intervention.

But we use our mental intervention, moving from step to step, until the movement flows without us.

When tranquil wisdom meditation becomes effortless, when it meditates itself without our involvement, we are finally ready for Zen practice. It’s time to leap from the One Hundred Foot Pole.

Christmas Humphreys’ commentary on the One Hundred Foot Pole koan explains that climbing to the top of the pole represents the height of thought. That’s what most of us have been doing throughout this program; we are thinking about the steps of the program, and then we think about them some more.

He then explains that leaping from the pole, after we have climbed to its top, represents the existential leap from thought to direct awareness.

[su_spacer size=”30″]

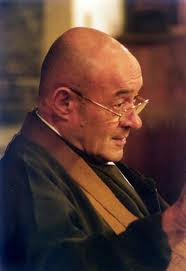

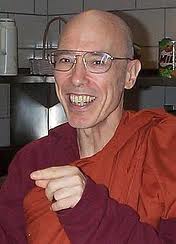

Christmas Humphreys, Founder of the London Buddhist Society

(1901-1983)

That’s what it means to break through the Zen barrier; we must go from thought to direct awareness.

We have to go from digital thought to analog direct awareness. From thinking about steps to letting go, and letting go, and letting go until the preliminary steps and the sixteen steps work without us.

We will experience the sixteen steps for the first time as we let go of the sixteen steps.

We shall not cease from exploration

And the end of all our exploring

Will be to arrive where we started

And know the place for the first time.

–T.S. Eliot

As professor Timothy Ferris observes in The Whole Shebang, any hack poet could have written the first three lines. Only a genius could have written the fourth.

The ninth step is awakening itself. The tenth step flows naturally from the ninth so this ninth step is the big one.

How can we break through the Zen barrier? And know the place -our mind- for the first time? Zen Master Mumon, referring to working on the koan “Mu,” said:

“Concentrate your whole self with its 360 bones and joints and 84,000 pores, into Mu and making your whole body a solid lump of doubt, day and night, without ceasing, keep digging into it. But don’t take it as “nothingness” or “being” or “non-being.”

“It must be like a red hot iron ball which you have gulped down and which you try to vomit up, but cannot.”

“You must extinguish all delusive thoughts and feelings you have up to the present cherished.”

“Zen means dropping off body and mind,” screamed Ch’an Master Ju-Ching at a monk who had dozed off during zazen.

And from the Diamond Sutra, the most famous exhortation of all:

“Arouse the mind without resting it upon anything.”

Do such exhortations really help? Are we missing something here?

The meaning of “Arouse the mind without resting it upon anything” is well-explained by Roshi Albert Low of the Montreal Zen Center in Zen and the Sutras.

We can meditate before breakfast, before lunch, before dinner, and before bedtime. But if we just sit in quietude, we are not arousing our mind and thus are not arousing our mind without resting it upon anything.

And that is the value of koan practice: It arouses the mind and the koan will not be solved until the aroused mind does not rest upon anything. The “solution” or “answer” to the koan doesn’t rest upon any Buddhist principle. It doesn’t rest upon logic or any other type of thought. It doesn’t rest upon Supreme Oneness because there is no Supreme Oneness out there nor is there one deep within. See Stephen Batchelor’s Confessions of a Buddhist Atheist.

Looking out and looking in both miss the Way. Neither subject nor object will ever be found. Emptiness includes no subject and no object. As we saw in the Hsin Hsin Ming:

If all thought-objects disappear

the thinking subject drops away.

For things are things because of mind,

as mind is mind because of things.

At 2:00 a.m., we can chant Master Hakuin’s Chant In Praise Of Zazen and we can sit until 2:30 a.m.

We can follow the example of Sensei Lawson Sachter, co-abbot of the Windhorse Zen Community; he set his alarm for 2:00 a.m. every night so that he could work on Mu in the middle of the night after having spent the day working on it.

Roshi Philip Kapleau eventually certified that Lawson had seen Mu, and proceeded to assign koan after koan thereafter. He passed all of them and became a fully sanctioned teacher as a dharma heir of Roshi Kapleau. He credits, at least in part, his 2:00 a.m. sittings.

When we catch ourselves daydreaming, we can recite The Ten Cardinal Precepts, we can recite The Four Vows, we can recall all ten of the Ten Great Vows of Bodhisattva Samantabhadra, or we can perform Buddha Name Recitations. That avoids wasting time on frivolity. As Roshi Kapleau said:

“Great is the matter of birth and death.

Life slips quickly by.

Time waits for no one.

Wake up! Wake up!

Don’t waste a moment.”

But really, how does one not waste a moment?

When feelings of lethargy arise, when we just want to lie down and take a snooze, we can follow Ajahn Brahm’s advice and do exactly that. But when we are rested, we can hit the meditation mat.

After all, the last words of the Buddha were:

“All compounded things decay. Work out your salvation with diligence.”

But how is that done?

Venerable Ajahn Brahm teaches that many mind objects may be contemplated after the meditator has emerged from the jhanas because the mind has acquired what he calls “super power mindfulness.”

Of course his use of the term “super power” jokingly refers to the super powers of various cartoon characters, but the idea of mindfulness being so strong that it is super powerful is a perceptive observation.

A Zen koan is a mind object. (Until it isn’t)!

Therefore, super power mindfulness can be used to work on a Zen koan that has been assigned by a teacher. After struggling with koans for years, we can develop super power mindfulness by following the Buddha’s sixteen steps and at last finally demonstrate to our teacher that the koan has been solved.

Although this website is called How To Practice Zen, until now we have obviously been learning primarily about Tranquil Wisdom meditation as taught in the Pali Canon. But we have been leading up to the Zen practiced by the Rinzai sect.

Harnessing the power of super power mindfulness is the key to cracking open a Zen koan. Without it, a Zen student can struggle a lifetime with koans and never open the gateless gate. With it, the koans are seen and the gate opens.

Tranquil Wisdom meditation provides the super power mindfulness required for koan penetration.

We will never hear that observation from a Theravada teacher because they ignore koans.

We will never hear that observation from a Zen teacher because they ignore Tranquil Wisdom meditation.

Most Zen students are assigned counting the breath as taught by Master Hakuin as their first practice, and then they are given a koan to solve.

No Zen teacher tells a Zen student to develop super power mindfulness as taught by the Buddha in the Anapanasati Sutta for koan penetration. If you are a Zen teacher who has taught tranquil wisdom meditation to students to develop super power mindfulness for the purpose of penetrating a Zen koan, (before learning that technique here, of course) please Contact Us.

The Buddha, Bhante U. Vimalaramsi, and Venerable Ajahn Brahm have given us the key to super power mindfulness. That’s what we have when we finish the sixteen steps.

An authentic Rinzai Zen practice can now begin. We practice the preliminary steps to put mindfulness up front and then we practice the sixteen steps that lead to super power mindfulness.

We then turn our super power mindfulness onto our teacher-assigned koan. We demonstrate that koan and the teacher gives us another one and we demonstrate it as well.

Over and over, the koans keep coming and we show every one of them to our teacher by subjecting the koan to the super power mindfulness generated by Tranquil Wisdom meditation.

Failure to penetrate a koan then is understood as simply practicing without super power mindfulness.

We reach the source by penetrating every koan our teacher assigns to us.

And when that happens, we become a dharma heir of our teacher and that takes us to the first dharma realm. A certified Zen teacher who receives full dharma transmission from a certified Zen teacher who received full dharma transmission, and so on, joins the line of mind-to-mind dharma transmission that began with the Buddha Shakyamuni.

Our practice never ends. We carry it into the marketplace, into the hustle and bustle of daily life.

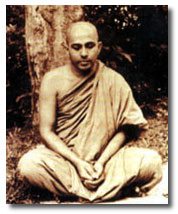

In A Still Forest Pool, the authors relate a story about the time when Venerable Ajahn Chah of Thailand was approached by a monk who had spent three years in his monastery.

The monk announced that he would be moving on to another monastery because he wanted to practice under an enlightened master. He told Ajahn Chah that he noticed that on some days the master was cheerful, friendly, and soft, yet on other days he would seem hard and unapproachable. His moods seemed to swing up and down, just like those of a normal person.

“How can I obtain enlightenment when my master himself is not enlightened?” the monk asked.

Ajahn Chah smiled.

“See, there you go again,” said the monk, “acting like you’re pleased that I’m leaving.”

“I’m smiling because I am happy,” said the great master. “This is a wonderful day. Today, after wasting three years, you will finally begin your spiritual practice.”

“You have been watching me, looking for the Buddha.”

“Today you have finally learned that you will never find the Buddha outside yourself.”

The monk performed a prostration and returned to his meditation hut. He understood the Buddha Dharma for the first time.

(1918-1992)

Many people wonder about the meaning of: “If you meet the Buddha on the road, kill him.” It means to kill the notion that the Buddha is outside ourselves; if we think we have found the Buddha outside ourselves, we must drop that thought.

We will never find the Buddha on the road, in a book, or on a website. However, if we work hard and diligently follow the steps of this course, including working with a sanctioned teacher, we will find the Buddha.

But the Buddha is emptiness, the Buddha has no self. Zen practice does not purify a self so that it can become a Buddha. Zen practice brings suffering to an end because only a self can suffer.

Super power mindfulness, the result of following the Buddha’s sixteen step Tranquil Meditation, penetrates koans.

We do not look for a savior outside ourselves nor do we seek a kingdom of heaven within ourselves. We awaken to no-self.

The Ox-Herding Pictures follow a cycle from beginning to end, and the end is the beginning. Who seeks the Ox? Who finds the footprints?

Our inherent Buddha nature seeks the Ox and finds the footprints.

But what is the point of realizing Buddhahood? It is not to selfishly acquire freedom from suffering for oneself because there is no independent self.

The point of attaining Buddhahood is to relieve the suffering of all sentient beings. This is done in our daily life by following The Precepts and maintaining our daily practices with diligence.

An authentic Zen practice creates super power mindfulness and that super power mindfulness mends the rip in reality created by delusion, knitting reality back to its oneness.

Beginnings and endings return to their original beginningless beginning and endless ending, the dharma realm of the Buddhas, free of mortal thoughts.

We have started a Zen practice, but we have to sustain it every day. It’s easy to slide back, like an upstream-bound rowboat drifting downstream when the oars are not used.

Upon harnessing super power mindfulness to penetrate koans, the bottom will drop out of the bucket. As Roshi Phillip Kapleau said, he felt like a fish swimming in cool, clear water after having been stuck in glue.

We will understand, for the first time, Yuanwu’s words, found in Zen Letters:

“Fundamentally, the Path is wordless and the Truth is birthless. Wordless words are used to reveal the birthless Truth. There is no second thing. As soon as you try to pursue and catch hold of the wordless Path and the birthless Truth, you have already stumbled past it.”

What does: “There is no second thing” mean? It means that nothing has ever happened.

This is the secret that Zen practice reveals: There are no secrets because everything is obvious. Nirvana is openly shown to our eyes. If we use our discriminating, thinking mind, the mind that divides everything into parts, then we make it hidden and non-obvious. We do that to ourselves; no one is doing it to us.

Having eaten the forbidden fruit, we now believe that we are independent entities having a birth date when we entered into existence and that we will have a death date when we exit existence. We have fallen from the garden of wisdom into the badlands of ignorance. We have to empty the cup of nonsense, of delusion, and super power mindfulness does exactly that.

There are no seams in a stupa. There are no beginnings nor are there endings. As the third patriarch of Zen says in the Hsin Hsin Ming, there is no yesterday, no tomorrow, no today. Reality is indivisible and completely empty; we can divide it in our minds, but it is our mind that gets divided, not emptiness. It’s like time; we say it is limited but it is the delusion we call “us” that is limited. Time is inexhaustible; use up quadrillions of years, and nothing has been used up.

Our Buddha nature is the same way. Nothing is there to get used up.

The Chaukhandi stupa, Sarnath, India

Judging, dividing good from evil, today from tomorrow, life from death, creates the thinking mind, the self that is separate from the whole, the self that expels itself from the garden, the self that is a collection of mortal thoughts.

And mortal thoughts are the opposite of super power mindfulness just as ignorance is the opposite of wisdom.

The second step of the eightfold path is Right Thought. Right Thought does not run towards what it likes and away from what it dislikes. It follows the Middle Way, neither liking nor disliking, free of judgment.

We left the Garden of Eden because we chose to choose, to weigh, to decide, to activate our thinking mind, thereby losing our inherent super power mindfulness. No one kicked us out of the garden. No one observes us and decides if we should be punished or rewarded.

The law of cause and effect is real. We create our own experiences. Nothing could be more obvious.

We experience our inherent Buddhahood by dint of diligent daily practice, including emptying the cup of mortal thoughts, and not engaging in philosophical or religious speculation.

This is the birthless truth, known by those who have established an authentic Buddhist practice. Only those with sharp karmic roots will understand this birthless truth and maintain their practice with diligence.

This website provides step-by-step instructions that anyone can follow, but few will. As the Bible wisely points out, broad is the path that leads to destruction (ignorance), but narrow is the path that leads to salvation (awakening).

Reaching out to grab enlightenment is a sure way to miss it. Zen teachers often tell the story of a young monk who asked a Zen master:

“How long will it take me to attain enlightenment?”

The master thought for a few moments and replied: “About ten years.”

The young monk was upset and said: “But you are assuming I am like the other monks and I am not. I will practice with great determination.”

“In that case,” replied the Master, “twenty years.”

A grasping, ambitious mind is an impediment to enlightenment.

Zen practice is not about aiming at a target and trying to hit it or setting a goal and trying to attain it.

To the contrary, Zen practice is about letting go. As the Buddha said, the twelfth step of the sixteen steps is to liberate the mind. This means to let go, to fall into the nimitta. And that leads to super power mindfulness and that enables penetration of koans and that leads to Nirvana.

In the practice of Zen, we create the conditions that allow enlightenment to happen. And then we let go and experience the Incomprehensible Unconditioned State of Ultimate Reality – and by naming it we have stumbled past it.

Remember T’zu-ming, who would stab himself in the thigh with a sharp tool when he felt himself becoming drowsy?

That’s the kind of dedication it takes to wake up.

Master Hakuin in Wild Ivy tells of a time when he and another monk vowed to sit for seven days together without eating or sleeping. They placed their mats a few inches apart and faced each other. They put a bamboo stick between the mats and agreed that if either meditator saw the other one getting sleepy, he was to pick up the stick and whack the sleepyhead between the eyes.

Master Hakuin reports that for seven days, neither monk so much as flickered an eyelash; the bamboo stick was never used.

The Buddha, having sought without success a teacher who could point the way to enlightenment, vowed that he would sit under a Bo tree until he either died or woke up.

It takes the determination of a Hakuin, a Tzu-ming, a Buddha to wake up.

Hakuin praised a book entitled “Breaking Through the Zen Barriers.” Note the plural in “Barriers.” Solving the koan “Mu!” is not the end of practice. Many koans must be passed. Many barriers must be broken through.

There is no beginning to practice, no end of enlightenment.

So for our ninth step we perform our Beginning Zen steps to put mindfulness in front of us and then we segue into Tranquil Wisdom meditation.

Bhavana Society Forest Monastery and Meditation Center

We attain super power mindfulness, or we should say that super power mindfulness appears, and we penetrate our koans, one by one, until we see It.

What happened to Moses on the top of Mount Sinai? What is the burning bush that burned but was not consumed by the flames? Why did the bush say: “I am the Great I Am”?

If we sit twice a day and master Tranquil Wisdom meditation and put super power mindfulness to work, the answer will become obvious.

Zen teachers tell us to place our attention about three finger widths below our belly button and into the center of our body (called the hara or tanden in Japanese or the dantian in Mandarin). This is the site of the third chakra in Tantric Hinduism.

Despite our best efforts, there will come a time when the pleasant burning sensation we feel in our hara rises to the top of our head. Whenever I reported that event to my teacher during a dokusan he would bristle: “That’s not Zen! Return your attention to the hara.”

The hair of our head is the burning bush that burns but is not consumed. We have left the hara and climbed to the top of the mountain, the top of our head, home of the chakra our Hindu friends call the crown chakra.

And when we feel the flame burning, we hear what Moses heard (I am the great “I am”) and we know what he experienced. It may not be Zen, as my teacher insists, but it is real.

But my teacher is right. When we feel that burning sensation on the top of the mountain, and we feel that we are the great I am, we let go of that mortal thought, that makyo, and return our attention to the hara. That’s Zen.

(1200-1253)

I once read a sign on the grounds across the moat from the Imperial Palace in Tokyo. It said, in English: “No smoking, no bonfires.” I chuckled because it was so Japanese – saying “no fires” by prohibiting fires from the smallest to the largest.

We can keep a little bonfire burning in our hara all the time. It requires mindfulness but with effort the fire never goes out.

Keeping that bonfire burning throughout the day, and not just during times of formal sitting, is a deep mindfulness practice. Whenever we discover that the fire has gone out, we return our attention to the hara and get it going again.

One way to re-start or re-fresh the fire is to recite namo amituo fo throughout the day, using it as a bellows to make the flames stronger.

Keeping the fire going is the Buddhist equivalent of the Christian injunction to pray without ceasing. If we can keep our hara or dantian glowing warmly 24/7, we are in the neighborhood of Nirvana.

When we sit for a formal zen sitting, zazen, our hara is already on fire and we can glide through present moment awareness, metta, silent present moment awareness, awareness of breaths both long and short, awareness of the whole body of the breath and awareness of the breath of the moment, the single tooth of the saw, in just a short while.

Having established mindfulness of the body, the three other mindfulnesses flow freely, without effort, and we are soon ready to solve another koan.

There are four stages of enlightenment according to the Buddha. Stream Entry (sotapanna), the Once Returner (sakadagamin), the Non-Returner (anagamin), and Buddhahood.

The Buddha taught that Stream Entry was attained when the first three of the ten fetters were overcome (the belief in an independent self -sakkaya ditthi-, doubt, and belief that chanting, rites and rituals alone could lead to Nirvana).

It is not difficult for modern people to agree that chanting, rites and rituals alone cannot lead to enlightenment, nor is it difficult to overcome doubt in the Buddhadharma; practice rather quickly removes such doubt. Sakkaya ditthi is the biggest hurdle for most of us.

A once-returner is one who has cut the first three of the ten fetters (thus attaining stream entry) and loosened the fetters of sense-desire (greed, lust, aversion), and ill will. Notice that these two powerful fetters need only be loosened to graduate from stream entry to once-returner status!

We loosen the fetter of sense desire with Present Moment Awareness and Silent Present Moment Awareness. We loosen the fetter of ill will by practicing metta.

A non-returner has cut the five fetters of belief in a self, doubt, belief that chanting, rites and rituals alone can lead to awakening, sense desire, and ill will.

Our daily practice of metta/loving kindness reduces our ill will. Our daily practice of Present Moment Awareness, and Silent Present Moment Awareness reduces our sense desire and our daily Mindfulness of the Body, the Feelings, the Mind and Mind Objects eliminates our sense desire.

The path that leads from ignorance to Stream Entry is the Eightfold Path and the path that leads from Stream Entry to the Once-Returner and to the Non-Returner is the Noble Eightfold Path according to Venerable Ajahn Brahm, because now it is a noble one who is following it.

And full enlightenment requires dropping the desire to experience the world of form, attained through the jhanas (fetter number six), and the world of formlessness, attained through the immaterial attainments (fetter number seven). And then conceit (fetter number eight), restlessness (fetter number nine), and ignorance (fetter number ten) must still be overcome.

When we drop all of the fetters, we discover that we created the fetters.

And we discover that we created the notion of a self that needed to drop fetters.

As R.E.M. says: “Oh, no, I’ve said too much. I haven’t said enough.”

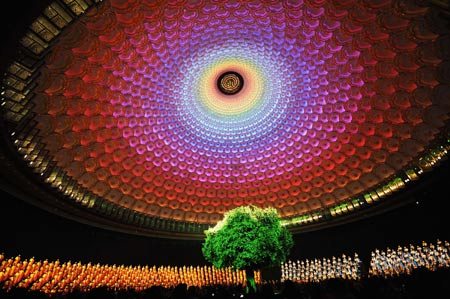

The Second World Buddhist Forum

Step Ten – Returning to the Marketplace

The First Dharma Realm

Barefooted and naked of breast, I mingle with the people of the world. My clothes are ragged and dust-laden, and I am ever blissful. I use no magic to extend my life; Now, before me, the dead trees become alive.

The first dharma realm is the dharma realm of the Buddhas. The central practice of this dharma realm is teaching the Buddha Dharma but that practice does not lift us to a higher dharma realm because there is no higher dharma realm.

Here is a recap of the central practices of all ten dharma realms.

Those of us who work on this course every day may not have attained the status of awakened masters, but as the tenth step of our program, we teach by example.

We become awakened masters if we master Tranquil Wisdom meditation and our teacher certifies that we have passed all assigned koans.

The Dharmacakra (wheel of dharma)

If we are traditional Rinzai Zen students working on teacher-assigned koans, in step nine we harness the super power mindfulness created by Tranquil Wisdom meditation to penetrate those koans and in step ten we teach other individuals on a one-to-one basis if we become sanctioned teachers.

Until we pass all our koans, we let our daily practices and our daily activities be our teachings.

If a Theravada practitioner masters Tranquil Wisdom meditation, he or she will have no problem with Zen koans.

An awakened master spreads enlightenment by mingling with humankind. Maybe even with animals, insects, and dull rocks as well.

How do dead trees become alive? We are the dead trees of whom the Master speaks. An enlightened Master works to awaken the dead trees – those of us who are asleep.

Many of us will not reach the stages of Reaching the Source and Returning To The Marketplace in this lifetime. But Returning To The Marketplace is the goal we reach without striving to reach it, without leaving home, without embarking on a self-improvement project.

We just practice, because the journey is the destination.

The Buddha maintained his practice for forty five years, i.e., from his enlightenment at age 35 until his parinirvana at age 80.

This is what an awakened Zen Master does: He or she lives in the world, teaching by example.

This is the highest, the first of the ten dharma realms – the realm of the Buddhas. It is “attained” only by the fully awakened.

I practiced with Roshi Aitken and other members of the Honolulu Diamond Sangha at the Palolo Zen Center on the last Sunday of his life, August 1, 2010. He was unable to sit at the mid-week Wednesday sitting and passed away that Thursday the 5th of August. So the Sunday sitting, my first and last with him, was his last group sitting. He was 93.

He practiced every day and inspired thousands of others to practice as well. We too can inspire others.

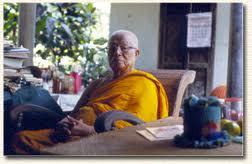

Robert Aitken Roshi, author of Taking the Path of Zen, was the first American who received full dharma transmission from the lineage of Japanese Zen masters Harada and Yasutani. During his lifetime, he passed that same dharma transmission to a small number of practitioners who are identified in the hyperlink associated with his name.

Robert Aitken, Roshi, Founder of the Buddhist Peace Fellowship and the Honolulu Diamond Sangha

(1917-2010)

Some members of the Diamond Sangha advised me that Philip Kapleau Roshi had completed about one-third to one-half of the koan course provided by masters Harada and Yasutani before he left Japan. However, he received permission to teach in a formal ceremony, a photograph of which appears in The Three Pillars of Zen, so there was no requirement that he demonstrate penetration of all of the Harada-Yasutani koans. He had reached the point where further koan study was worthless.

Teachers in the Soto sect are more numerous than Rinzai sect teachers since authority to teach is given after ten years of sustained practice in a Soto Zen community such as the San Francisco Zen Center. However, there are still very few people who have completed such a rigorous requirement.

In a nation of over three hundred million people, we have less than three hundred certified Zen teachers. That’s less than one per million.

So whether we follow the Rinzai/koan or the Soto/shikantaza route, the tenth practice is to teach upon being given the authority to do so or to encourage others to practice if we are not yet sanctioned teachers. We can become a Zen Practice Foundation Certified Lay Teacher if we meet certain rigorous requirements.

We really shouldn’t say Rinzai or Soto. Rinzai masters assign shikantaza to their students who have passed all koans, and modern day shikantaza masters assign koans to their students just as Master Eihei Dogen did.

(Replica temple in Hawaii; the original is in Japan)

The term “teach” in the Zen sect refers to individual instruction of the type that occurs during dokusan (that’s the Soto Zen term; in Rinzai Zen it’s called daisan). The teacher determines what needs to be done or said at that moment in dokusan or daisan to guide the student toward enlightenment. Sometimes no words are exchanged.

Books or websites about Buddhism are directed to a broad audience for the benefit of all sentient beings and are not the kind of individual, customized teaching that requires formal Dharma Transmission. For example, a koan should be assigned to a student only by a sanctioned teacher and the student and teacher need to work together in person until the koan is “solved.” And that may lead to another koan, or another practice entirely…

But the rest of us can refer others to this and other Buddhist websites or blogs and we can start sitting groups. We can rent or buy a house and convert it into a zendo, we can start a Buddhadharma talk show on local radio or TV, we can write articles for our local newspaper, write magazine articles or a book, and so on.

We can also enroll in and complete the Dedicated Practitioners Program or the Community Dharma Leaders Program at Spirit Rock, a Theravada practice center about thirty five miles north of San Francisco.

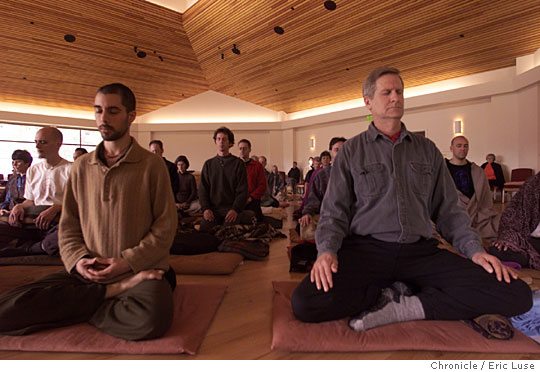

(The practitioner on the right is in the Burmese position; note the support under the left knee. It is important that both knees touch the ground or other support such as shown here. The practitioner on the left is in either full or half lotus with hands in the classic Zen position, left hand on top, thumbs touching lightly.)

But the most important teaching we can provide to fulfill this tenth step is to carry our Zen practices into the marketplace every day.

Our classmates, customers, patients, clients, co-workers and everyone else we deal with are our teachers and they are in the dokusan room we enter every day.

The traditional commentary says that this tenth and final stage is the step of attaining full Buddhahood. We may therefore conclude, without speculation, that it corresponds to whatever it is that lies beyond the four jhanas and the four immaterial attainments, i.e., Nirvana.

The Buddha never referred to Nirvana as the ninth jhana or the fifth immaterial attainment. He said there were four jhanas, four immaterial attainments, and Nirvana. And that until we experience dependent origination, both forward and backward, we can’t know Nirvana.

Although memorization is far from realization, memorization has value. For certification as a lay teacher, we recommend memorization of:

The Repentance Gatha

The Three General Resolutions

The Three Refuges

The Four Vows

The Four Brahma Viharas

The Four Noble Truths

The Five Hindrances

The Six Paramitas

The Seven Factors of Enlightenment

The Eight Steps of the Eightfold Path

The Ten Vows of Bodhisattva Samantabhadra;

The Ten Precepts

The Twelve Links of Dependent Origination

The title and verse of each of the ten ox-herding pictures; and

All of the chants.

The concept of ten dharma realms is a Mahayana concept not held by the Theravada school; as mentioned earlier, thirty one dharma realms are described in the Pali canon and Nibbana is not considered one of them. Nor does the Theravada school subscribe to the ten ox-herding pictures – the pictures are from the Zen sect of the Mahayana school.

By the same token, the Mahayana school and the Zen sect ignore the four jhanas and the four immaterial attainments as described by the Buddha so there is no direct correlation between the ten dharma realms and the stages of meditation as taught by the Buddha.

The word jhana is the Pali word for the Sanskrit word dhyana that was transliterated into Chinese as Ch’an and into Japanese as Zen. So it is ironic that the jhana sect ignores the Buddha’s teachings about the jhanas!

(My wife once asked a well-known Zen sensei what he thought of jhana meditation. He had never heard of it).

Nor is it traditional to correlate the ten dharma realms and the ten Ox-herding pictures. We have conflated them merely as a teaching tool; it helps us learn about both when we visualize them in matching pairs, i.e., leaving the tenth dharma realm of the sad but impermanent hell worlds by practicing the cultivation of happiness when we begin our search for the ox, leaving the ninth dharma realm of the hateful hungry ghosts by cultivating Loving Kindness as we find the footprints, and so on.

The jhanas are not indispensable, however. As the Buddha made clear in the Satipatthana Sutta, practice of the Four Foundations of Mindfulness and awareness of the Seven Factors of Enlightenment also provide a “direct path” to Nibbana, without experiencing the jhanas. This is known as “dry insight.” See Breathing Through The Whole Body by Will Johnson.

As Jack Kornfield points out in his introduction to Mindfulness, Bliss and Beyond, there are many practices that lead to awakening, not just the tranquil wisdom meditation taught in the Anapanasati Sutta. He mentions the teachings of Zen Master Thich Nhat Hanh, Tibetan master the Dalai Lama, Venerable Ajahn Buddhadasa, and Venerable Sunyun Sayadaw who offer “different and equally liberating perspectives.”

Theravada teachers often instruct students to begin a sitting with samatha (calmness) meditation, and when the mind is calm, to begin vipassana (insight) practice. Others argue that a practitioner should do either samatha or vipassana but not both.

Some works on Theravada Buddhism contend that samatha practice cannot lead to Buddhahood and that vipassana is the only practice that is valid.

Other books on the same subject hold that the Buddha himself practiced samatha, not vipassana.

Still other writers argue that the practices of samatha and vippasana are not really different meditations at all, that deep samatha practice naturally leads to vipassana practice. Ajhan Brahm, in Mindfulness, Bliss and Beyond, is one of the teachers who argues that the practices are not distinct from one another.

If it is true that the Buddha performed only jhana practice, then it is obvious that those who announce that jhana practice cannot lead to enlightenment must be mistaken.

Koan practice, favored by the Rinzai sect of Zen, is not mentioned in the original Buddhist writings. However, many Zen practitioners have attained enlightenment through koan practice and Zen teachers assure us that koan practice is the most effective meditation technique.

Jhana, vipassana, and koan practices are all authentic; they are just different and none of them should be ignored.

Zen master Robert Zenrin Lewis, of the Jacksonville Zen Sangha, like Jack Kornfield, also agrees that there are many paths to awakening. “Choose one!” he exhorts.

But in this course we have chosen two methods and combined them. We develop “super power” mindfulness by following the Theravada Tranquil Wisdom meditation and we harness that super power mindfulness to enable us to demonstrate to our Sensei or Roshi (a Sensei for many years) that we have penetrated the koans assigned to us.

Practitioners of Zen koans, shikantaza, counting the exhalations meditation, and other forms of meditation may attain enlightenment while ignoring the sixteen steps of Tranquil Wisdom meditation, the Four Foundations of Mindfulness and the Seven Factors of Enlightenment.

But most Zen students spend their entire lifetime trying to penetrate a single koan or sitting in shikantaza to little or no effect. With super power mindfulness generated by following the Buddha’s instructions, koan and shikantaza practice will bear more fruit.

I have never heard any Theravada teacher suggest that the super power mindfulness generated by a jhana experience could be harnessed to penetrate a koan.

Nor have I heard of a Zen teacher instructing a student to develop super power mindfulness by following the Buddha’s sixteen step meditation so that a koan could be penetrated.

Kiyomizu (Clear Water) Tera, Kyoto

So it seems that the Theravada school has developed a tool of which Zen teachers are unaware, and the Zen school is unaware that the Theravada has a tool that the Zen school could use.

The Buddha said that true liberation requires experience of dependent origination, both forward and backwards. A practitioner who follows the precepts will see – someday – dependent origination, forward and backward, upon diligent practice of vipassana/insight meditation, samatha/samadhi or calming meditation such as tranquil wisdom meditation, koan practice, counting the breath, loving kindness meditation, or shikantaza.

But by harnessing super power mindfulness and using it for koan practice, that someday becomes now. Working without the proper tool makes the work much harder.

In the first nine steps of this course, each step has a central practice that takes us to the next level. The central practice is an antidote to the causes and conditions that take us to and bind us to that particular dharma realm.

But as mentioned above, there is no central practice to lift us from the first dharma realm because it is the Buddha dharma realm and nothing lies above it.

If Nibbana is outside of all dharma realms as taught by the Theravada school, then reality has a split formed in it, i.e., there is a dichotomy.

If Nirvana is the first dharma realm and the beings who attain it are no longer beings at all and cannot re-enter the evil dharma realms, as taught by the Mahayana school, the dichotomy again appears.

So we can look at the dharma/dhamma realms as not being clearly defined and as extending infinitely in both directions from the crude to the subtle. No hottest hell, no best heaven. No bottom at one end and no top at the other.

Or we can take the position of The Heart Sutra, the ultimate Zen sutra, and see the emptiness of all dharmas, all dharma realms.

Nor is there pain,

Or cause of pain,

Nor noble path to lead from pain,

Not even wisdom to attain.

“Nor is there pain” denies the First Noble Truth, the truth of dukkha.

“Or cause of pain” is a denial of the Second Noble Truth, that dukkha is caused by desire (tanha) conditioned by ignorance (avijja).

“Nor noble path to lead from pain” is denial of the Third Noble Truth that suffering/pain (dukkha) can be brought to cessation (nirodha).

“Not even wisdom to attain” is denial of the Fourth Noble Truth that wisdom is attainable by following the Noble Eightfold Path.

Here we see another difference between classic Buddhism and Zen. The former says we have to do the work, i.e., follow the eightfold path until we attain wisdom/enlightenment, and the latter says: No, our inherent nature is Buddha nature, we already have wisdom, we merely have to uncover it.

But we uncover it by following the eightfold path.

So all we really have is just a play on words, discursive thinking creating a chasm where none exists.

So if we sit in tranquil wisdom and reach the realm of neither perception nor non perception, and then fade away into Nibbana, never to be re-born into “existence” again, what if that final cessation, that liberation from existence is merely entry into the lowest Nibbana…

But the Mahayana teaching is that no independent self exists so there is no one to enter into Nibanna. Anuttara samyak sambodhi is extinction of self as taught by the Theravada, but neither extinction of self nor eternal existence of self as taught by the Mahayana.

The Mahayana explanation is understood if we accept the Mahayana premise that nothing is independent of anything else, that reality is indivisible and empty of individual entities who stand outside of reality.

If reality is indivisible/empty of independent individuals, then no independent individual can enter reality at birth or depart it at death. Nor can an enlightened Buddha leave reality because even Buddhahood is empty of self – nothing stands alone, outside of reality. There are no two things.

That’s why Zen masters tell us we are whole and complete just as we are. From the very beginning, all beings are Buddhas.

But we have to cultivate/practice Zen to realize the truth of that statement. Otherwise, it’s nothing but a belief and our Buddhism has the stench of blind belief religion.

Every time I hear a newborn baby cry, or touch a leaf, or see the sky, then I know why I believe!

–Lyrics written by an incredibly stupid person in a popular song of the 1960s

With practice comes the awareness of Buddhahood but that awareness is not owned or experienced by an independent being.

There are several important Buddhist practices that support our central practices, even though none of the auxiliary practices, standing alone, can lift us from one level of realization to another.

So we reserve discussion of these auxiliary practices for this tenth and final step of the How To Practice Zen program. Buddhists all over the world practice these auxiliary steps. They are non-meditation steps but they support our meditation practice.

Moreover, if performed mindfully, these steps can become meditation steps as well. We begin with chanting.

Chanting

Chanting is an important part of an authentic Zen practice.

Learning chants takes a lot of time but is well worth the effort. When memorized, the chants become a part of us. A chant or a part thereof can be summoned at any time, any place; we won’t need to carry a chant book with us if we have committed each one to memory.

Roshi Philip Kapleau said:

“Mind is unlimited.

Chanting, when performed egolessly,

has the power to penetrate

visible and invisible worlds.”

Chanting also has the power to lift us from the realm of desire into the heavenly realms.

Roshi Kapleau advised against forced memorization, advising us to chant daily and to let the memorization happen gradually. However, some people who have practiced for more than ten years still reach for a chant book when a chanting service begins. Obviously, gradual memorization doesn’t work for everybody.

Roshi Kapleau further advised us to chant in a voice near the lower end of our range. So we chant with a low pitch but not with a growl. When chanting with a group, we try to harmonize with the group. We chant in a monotone, without emphasizing syllables. This helps keep the mind on an even keel. A sing-songy, emotion-driven rendition of a chant dilutes its power.

I once had to lead a chant at a Vesak ceremony at a Unitarian-Universalist congregaton (held in May at about the time of the first full moon to observe the Buddha’s birth and in some countries his death and enlightenment as well) because no one else in our Zen group would do it. My plan was to open the chanting session by asking the audience – a non-Buddhist crowd – to chant with our chanters – a team assembled from our local Zen center – in a low voice, but not so low as to be a growling voice. However, we were preceded in the program by a Tibetan monk who chanted the Heart Sutra in one long growling growl; it was quite pleasant and well-received but of course I had to change my opening remarks.

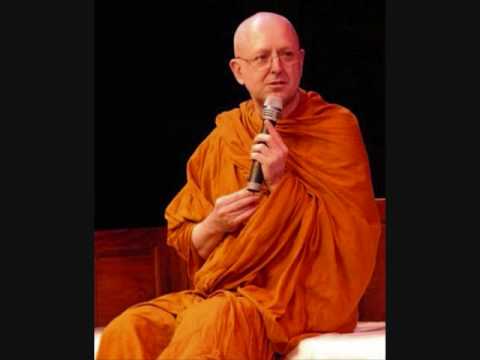

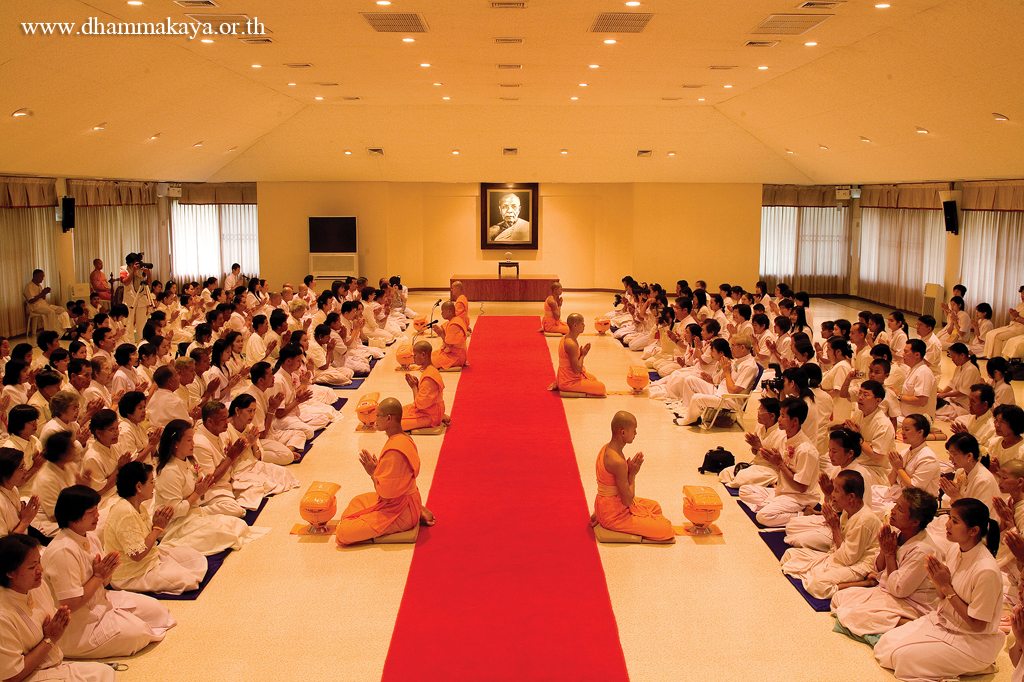

Vesak Day at Wat Phra Dhammakaya

To chant, we kneel on a mat, with back straight and knees forward, spread apart at a distance that is comfortable, and sit on our feet. This is the seiza position mentioned in Creating a Practice Space in Beginning Zen. We place our right hand in our lap, palm up, and then place our left hand, palm up, on top of the right hand with the thumbs crossing, not touching at the tips.

Subject to the exception of Master Hakuin’s Chant In Praise Of Zazen, chants are chanted to the beat of a mokugyo (Japanese for wooden fish). You can purchase a small one for home use at The Monastery Store. Most Zen centers also have a large bowl-shaped gong known by its Japanese name, keisu, as well as a small one for use in chants.

The photo on the left shows a mokugyo and a keisu is on the right:

The drumstick of the mokugyo is stored in a slot in the back of the instrument. Only the drumhead is visible in the photo. There is a bit of history behind these pictured items.

All of the chants and more are in bound form and can be purchased for a nominal fee at the marketplace of the Rochester Zen Center.

On the subject of chanting, it is worth noting that many Chinese Ch’an/Zen masters promote both the practice of Zen chanting as well as the practice of Pure Land (Jin Tu) chanting.

We recommend Master Hakuin’s Chant in Praise of Zazen as the first chant to learn.

This very famous chant, written in the 1700s by Japanese Master Hakuin during his work to revitalize Zen practice in Japan, follows a logical flow, beginning with: “From the very beginning…” Therefore, it is not difficult to memorize.

Master Hakuin’s chant is chanted, as aforesaid, without the beat of a mokugyo, the wooden fish drum used in other chants. It is customarily chanted prior to a Teisho at retreats. However, it is so deep and so instructive that daily repetition is invaluable.

If our first thought every morning is to fire up the coffee maker, or to check Facebook, or to turn on the news, we can try chanting In Praise of Zazen instead. The things that concern us gradually fade away as we tune into higher planes of consciousness.

Master Hakuin’s Chant In Praise of Zazen

From the very beginning, all beings are Buddha.

Like water and ice, without water no ice,

outside us, no Buddhas.

How near the truth yet how far we seek,

like one in water crying “I thirst.”

Like a child of rich birth wand’ring poor on this earth,

we endlessly circle the six worlds.

The cause of our sorrow is ego delusion.

From dark path to dark path we’ve wandered in darkness —

how can we be free from birth and death?

The gateway to freedom is zazen samadhi–

beyond exaltation, beyond all our praises,

the pure Mahayana.

Upholding the precepts,

repentance and giving,

the countless good deeds,

and the Way of right-living

all come from zazen.

Thus one true samadhi extinguishes evils;

it purifies karma, dissolving obstructions.

Then where are the dark paths to lead us astray?

The pure lotus land is not far away.

Hearing this truth, heart humble and grateful,

to praise and embrace it, to practice its wisdom,

brings unending blessings,

brings mountains of merit.

And when we turn inward and prove our True-nature —

That True-self is no-self,

our own self is no-self —

we go beyond ego and past clever words.

Then the gate to the oneness

of cause and effect

is thrown open.

Not two and not three,

straight ahead runs the Way.

Our form now being no-form,

in going and returning we never leave home.

Our thought now being no-thought,

our dancing and songs are the

voice of the Dharma.

How vast is the heaven

of boundless samadhi!

How bright and transparent

the moonlight of wisdom!

What is there outside us,

what is there we lack?

Nirvana is openly shown to our eyes.

This earth where we stand

is the pure lotus land,

and this very body the body of Buddha.

(end of chant)

If you want to be a Buddha, you must think like a Buddha – Dharma Master Hsuan Hua.

Daily chanting of Master Hakuin’s Chant will help us think like a Buddha. The day will come when the truth of this chant is realized and we will understand that this earth where we stand is the pure lotus land.

A Teisho is a talk by a sanctioned teacher, usually given during an intensive meditation retreat known by the Japanese term sesshin. The teacher sits on a raised platform and faces the Buddha altar, not the meditators. The teacher thus directs the Teisho to the Buddha, and this helps the teacher raise the Teisho to the highest level.

A Teisho is not a Dharma Talk which is a talk by a senior student who has not received sanction to teach. The speaker faces the sangha during the talk and sits on his or her normal cushions, there being no raised platform in use. Dharma talks are typically given during regular meetings of the meditation group and usually supplant a round of meditation. Master Hakuin’s chant is not recited prior to a Dharma talk.

Although Zen practitioners sit without motion during periods of formal zazen, most Zen centers have a rule that allows the listeners to adjust their posture during a Teisho or a Dharma talk because listening is the paramount activity during either talk.

The “six worlds” refers to the bottom six worlds of the ten dharma realms. This is the desire realm that we find ourselves in. A sentient being in the desire realm is subject to visiting the other five realms in one lifetime and is subject to re-birth in any one of the six realms. Only the sentient beings of the top four realms are immune to falling into the desire realm.

Samadhi is Sanskrit and is usually translated as concentration but it is a high degree of concentration, one-pointedness, that is often experienced as spiritual bliss. Every meditator eventually experiences it except those who meditate while ignoring the precepts and the third, fourth and fifth folds of the eightfold path. Samadhi is called kensho in Japanese.

Having a samadhi experience does not mean that one has attained enlightenment.

There are many different levels of samadhi. The experience may be brief in time or lengthy. It may be deep or shallow.

Master Hsuan Hua was meditating one night in a hut he built by his mother’s grave as an exercise in filial piety. A bright light shot out of the hut and the townspeople grabbed buckets of water and ran to the cemetery to douse what they thought was a fire. The hut was ablaze with light when they arrived. The Master was sitting inside, in samadhi, emitting light. There was no fire.

Sitting in meditation in Taipei, Taiwan in August, 1979, I heard a beautiful flute playing. A window was open and I was certain that a musician was in the street. I got out of my posture and looked out the window, but no flute player was there; just the usual street scene.

I then realized that I had heard the flute of Krishna of which our Hindu friends speak. Still in a meditative mood, I sat back down, certain that the music would return and it did.

I listened to it for awhile, and it was beautiful. I will remember this sublime, unforgettable tune forever, I thought. And I will record it and Paul McCartney, eat your heart out! I’m going to be rich!

Need I add that the music stopped and I can’t recall a single note of it?

Zen masters have a colorful term for a samadhi experienced in the absence of wisdom: they call it Dead Tree Samadhi.

Master Hakuin’s chant also employs that oft-heard word, “karma.”

Karma is a Sanskrit word meaning “action” but it is perhaps better understood as meaning “the law of cause and effect.” Every action produces an effect. Karma, not God, controls the universe. Yes, there are sentient beings in the heavenly worlds but they are not our judges.

The law of cause and effect is like the law of gravity: It extends everywhere, it never stops working, and there is no brain behind it.

No god sits in judgment, deciding to punish us when we are bad and deciding to reward us when we are good.

Thanks to the law of gravity, we trip, we fall. Karma works the same way. Punch other people in the nose and get punched back in return. Help others, receive help.

What is the most obvious observation that anyone could ever make? Here it is, the open secret of the six worlds, the realm of desire:

Everything that (apparently) happens is the result of everything that has been done.

It can’t be otherwise. Effects cannot appear without a cause. And every effect then become the next cause.

Stephen Hawking tells us that in the quantum world, causes may precede effects but such effects disappear in the larger, macro world.

And there is, apparently, no first cause because something earlier would have had to cause that first cause.

But the law of karma does not always operate in an obvious way. Sure, some simple karmic activities like kicking a brick wall while barefooted have immediate karmic consequences but it isn’t always so obvious.

Karma can even carry over from lifetime to lifetime, but that’s another subject.

We are the sum of all our thoughts. Scary as it may seem, all of us have thought ourselves into our respective predicaments. Where we are today is the result of everything we have ever thought from beginningless time and what we do today sets us on a course into the endless future.

But if there is no self, who experiences the results of a thought? Answer: Another thought experiences the result of a preceding thought.

We are simply the thoughts we cling to or identify with. Disengagement from thoughts arises from the practice of zazen and the practices that make effective zazen possible.

Do we perceive the world as one big loving family? Or as a mean place where terrorists lurk? Most of us see the world as a mixture of good and bad.

However, a person with little or no spiritual enlightenment will see the world as an extremely hostile place and a fully enlightened Buddha will see the world as Nirvana.

As one is, so one sees.

Next we encounter the term “Mahayana.” Mahayana is Sanskrit for Great Vehicle or Big Boat. Just as the protestants split from the original Catholic faith, so too did the Buddhist world split into two major schools. And the largest of those two also split many times.

Original Indian Buddhism had multiple schools but the only one that survived into the modern world is known as the Theravada school, the Way of the Elders.

Most of the other schools of Buddhism that survived to the modern world are grouped together under the heading Mahayana. Zen is one of the Mahayana schools. There are two major Zen schools, Soto and Rinzai, and a smaller school found mostly in Japan, Obako.

Tibetan Buddhism has its own category: Vajrayana. Just as Zen is a mixture of Mahayana Buddhism and Taoism (Wade-Giles), the indigenous “religion” of China, Vajrayana is a mixture of Mahayana and Bon, the indigenous religion of Tibet.

Zen is the second largest of the Mahayana schools. The largest Mahayana school is The Pure Land school and its practitioners in China and Japan greatly outnumber Zen practitioners.

Many Chinese Ch’an/Zen masters encourage Pure Land practices.

Zen was created by the merger of Indian Buddhism and Chinese Daoism (pinyin). None of the famous Zen sutras were spoken by the Buddha; they were written by enlightened Chinese masters who understood what the Buddha had said (and more importantly, experienced what the Buddha experienced) and placed the Buddha’s teachings into their own words.

Many of the Chinese sutras begin with: “Thus I have heard…” and what follows is the Chinese Master’s version of what the Buddha said. Scholars strongly suspect this to be the case because the Chinese Ch’an/Zen sutras are drastically different in style from the original Pali texts as preserved through the centuries by the Theravada school. (Pali is a dialect of Sanskrit: Sanskrit “nirvana” is “nibbana” in Pali; Sanskrit “dharma” is “dhamma” in Pali, and so on).

We even find, in one Chinese sutra, that the Buddha said: “How lucky it is to be re-born in human form. Luckier still to be re-born Chinese!”

Since the Buddha most likely never heard of China, and since the Buddha taught non-discrimination, it is a pretty safe bet that those words came from a Chinese master, no doubt giggling as he wrote with tongue-in-cheek.

Or the “Luckier still to be re-born Chinese” was simply a humorous commentary. The Chinese are very fond of commenting on every phrase of a sutra.

As practiced in the modern world, there are few differences between Theravada and the several schools of the Mahayana. Both Theravada and Mahayana schools meditate and Zen simply means “meditation” so what is the difference?

The meditation techniques are different and the two schools follow different rituals, but they both are essentially the same. The Zen sect simply emphasizes meditation more than the other sects. That’s why most Americans are attracted to the Zen sect. We are more interested in meditation than we are in rites and rituals.

I have attended multiple Sunday morning Chinese Buddhist services, and I am no longer amazed that they do everything except meditation.

Some Asian teachers tell the story of two people who come to a wall. They climb atop it, and both shout with joy at the sight they behold. Apparently, they see the land of milk and honey. (Perhaps considered hell by vegans!)

Delighted, the first person leaps from the wall and disappears into the promised land, never to be heard from again. The second person practices restraint and resolves not to pass over the wall until all sentient beings have crossed over. Only then will the selfless one enter into that happy land.

The first person is the Arhat, the selfish Theravadan who only wants to save himself. The second person is the Bodhisattva, the ideal of the Mahayana.

That is a mean-minded, unenlightened story! Sadly, in Asia the Mahayana followers really do look down on the Theravadans, who they dismissively call the Hinayana (Small Vehicle or Little Boat), implying that the Hinayana people are small-minded and somewhat selfish. After all, they do kill animals for food and think nothing of it.

This Asian problem has cultural roots. The Mahayana countries are China (including Tibet), Japan, Korea, and most of Vietnam, i.e., China and the countries that historically find themselves in the cultural orbit of China.

The Theravada countries are Sri Lanka (Holy Island), Burma, Thailand, Cambodia, Laos, and the Cambodian border area of Vietnam. Malaysia is primarily Muslim with a minority Buddhist population.

The story of a self-centered Arhat is ludicrous because an Arhat has attained perfect enlightenment. That of course cannot happen until the practitioner has developed the Bodhisattva spirit, vowing not to enter Nirvana until all sentient beings have done so.

The Arhat does not pass into Nirvana, never to be heard from again. Both people went back from that wall, compelled by compassion, to help others enter into the promised land. One of them, however, spread a rumor that the other had selfishly disappeared over the wall.

That, in a nutshell, is how Buddhism divided into a Northern or Mahayana school and a Southern or Theravada school.

In the United States, the two schools mix freely, each attending the other’s sittings, chanting services, and retreats. Very little mixing occurs in Asia, primarily due to the geographical distances, cultural differences, historical inertia, and language problems involved, none of which prevails in the States.

Although the Mahayana appears a little haughty if not arrogant in its attitude toward the Hinayana (actually considered to be a dirty word!), scholars say that the Theravada school preserved the Buddha’s original teachings but that Buddhism would not have become a world “religion” if the Mahayana had not transformed it from a “monkish” religion. As the Mahayana spread, Buddhism became a religion for lay people as well as monks and nuns.

Most scholars also agree that the split between Mahayana and Theravada occurred vey early, perhaps as little as one hundred years after the parinirvana of the Buddha.

Master Hsuan Hua, a modern day Ch’an master from China, was well aware of the prejudices held by many Mahayana practitioners against the Theravada practitioners so he worked hard during his lifetime to dispel such prejudices. He befriended Theravada practitioners and even gave them land to build a Theravada monastery near his own property (The City of Ten Thousand Buddhas) in northern California.

So even though we are speaking of starting and maintaining an authentic Zen practice, we mean no prejudice against other forms of practice. If we are lucky enough to live near a Pure Land or a Theravada practice center, by all means we should go there and practice. But we can skip the animal-killing that defiles the Theravada temples.

And when we practice Zen, we include selected Theravada and Pure Land practices.

If we ever make it to the City of Ten Thousand Buddhas, we can drive another eighteen miles and visit the Abhayagiri monastery, the Thai forest tradition monastery that received the gift of land from Master Hua.

When visiting Abhayagiri, I saw an alabaster Buddha on the hillside, overlooking the monastery, so I climbed a path to get closer to it for a photo. After taking the photo, I saw that the path continued around the side of the mountain so I started following it. After just a few steps, I encountered a sign that said something like:

Do not walk alone.

No jogging, no bike riding.

Beware of mountain lions.

I still regret that I didn’t have the presence of mind to photograph that sign. I just descended from the hillside without delay.

Hakuin also mentions “wisdom,” a word that pops up frequently in Buddhism and during sports casts.”The quarterback hit the tight end instead of the wide receiver, a wise choice. That’s the wisdom that comes with experience, folks.”

We often hear of Wisdom but the word is hard to define. In Buddhism, it simply refers to deep understanding of The Four Noble Truths.

Most writers say that The First Noble Truth is that life is suffering but the Buddha never said that. He said life is out of whack like a wheel mounted on an eccentric axle.

If the axle of a wheel is concentrically mounted, that means it is mounted in the center of the wheel and any vehicle carried by such a wheel will proceed smoothly in a level plane.

Mount the axle away from the center and the vehicle will go up and down as it proceeds. The amplitude of the up and down motion increases as the distance from the center of the wheel to the axle increases.

No doubt the Buddha had seen ox-pulled carts in his day, 2500 years ago, where the axle was eccentrically mounted and the wagon rose and fell with each rotation of such a wheel. He saw that imperfection in his daily life.

After attaining enlightenment under the Bodhi tree, he searched for a way to communicate to others what he had realized and settled upon the Pali word “dukkha” when announcing The First Noble Truth that life is unacceptable, unsatisfactory, out of whack like an eccentrically-mounted wheel, a dukkha wheel.

If we can penetrate The First Noble Truth, we know the other three.

Right Understanding, also known as Right View, is the first fold of the eightfold path.

Right Understanding of what? Of the First Noble Truth. Right Understanding is the cure for ignorance. In Buddhism, an ignorant person is a person who doesn’t know the First Noble Truth. Or someone who intellectually knows it, but does not really know it.

The Second Noble Truth is often stated as “The suffering of The First Noble Truth is caused by desire.”

Desire for what? Desire for a separate, independent self. From ignorance there arises a desire to withdraw, to separate, to know good and evil.

Red Pine tells us that the Sarvastidians, one of the early Buddhist sects who were contemporaries of the Theravadans, realized that the Four Noble Truths applied only to the six worlds. There could be no desire in the four heavenly realms.

The Biblical story of Satan being kicked out of heaven because he wanted to be a king just like God has the ring of truth.

Who is that nasty old Satan who wanted to have a separate self, who wanted a discriminating mind so that he (or it) could pick and choose between things it likes and things it doesn’t?

Do we know anyone who judges, who picks and chooses, who thinks he or she has a self that is independent of everything else?

When we judge, when we weigh, when we choose, when we like, when we dislike…that is the satanic mind.

We practice Zen to awaken to our original Buddha nature, thereby transforming our satanic nature which is so inbred in us that we don’t even realize how far our axle is from its central position. But no god or devil did it to us. We kicked ourselves out of paradise with our desire.

How successful we have been in creating the powerful illusion of a separate self. No one told us to be careful of what we wished, or if they did we ignored the advice. Can we click our heels three times and go home? There is no positive action we can take to propel us back into the Nirvana from which we emerged.

We can only practice Zen, thereby creating the conditions that allow us to return to our natural state.